| Genus List | Species List |

The genus Eurhopalothrix is a member of the monophyletic tribe Basicerotini (Bolton 1998). Eurhopalothrix occurs in the Neotropics and in the Indo-Australian-southwestern Pacific area (Brown and Kempf 1960). They are members of the "cryptobiotic" fauna: small, slow ants that live in rotten wood and leaf litter. They are predators, preying on small, soft-bodied arthropods (Wilson 1956, Brown and Kempf 1960, Wilson and Brown 1985).

Workers and nests are extremely difficult to see in the field, because the workers are camouflaged and very slow moving. On disturbance they freeze, often curling into a pupal position, and remain motionless for several minutes (Wilson and Brown 1985). As a result of their cryptic nature, they were considered extremely rare until the 1960's. But increasing use of Winkler and Berlese sampling has shown Eurhopalothrix to be relatively common. I encounter them in most Winkler samples from wet forest sites in Costa Rica.

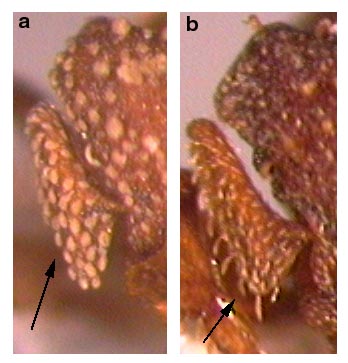

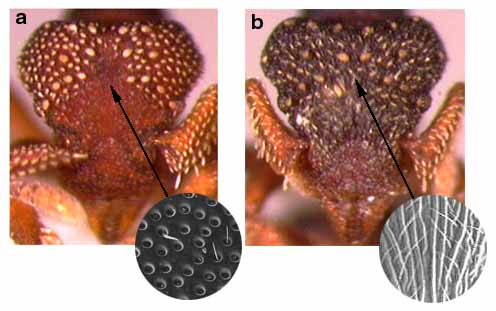

Workers usually have an appressed "ground pilosity" of filiform to spatulate setae, and a variable number of larger, specialized erect setae on the face, mesosomal dorsum, petiole, postpetiole, and gaster. The specialized setae vary from filiform to broadly spatulate to almost pompon-like, and may be straight or curled over. Hoelldobler and Wilson (1986) found this pilosity structure to be common to many basicerotines and to the genus Stegomyrmex, calling the ground pilosity "holding hairs" and the specialized erect setae "brush hairs" (see copies of their SEM figures under Basiceros manni and Eurhopalothrix bolaui). They observed that foragers (but not younger nest workers) commonly had an encrustation of soil adhering to the body surface, held in place by the holding hairs. They concluded that the soil layer served to camouflage the workers from predators such as birds and lizards, and that the adaptive significance of the bizarre pilosity was to capture soil particles (the function of the brush hairs) and adhere them to the cuticular surface (the function of the holding hairs).

Brown and Kempf (1960) revised the genus and provided keys. They were hampered by an extreme paucity of material, and from Costa Rica they knew of only two collections. Since then Snelling (1968) described a new species from El Salvador; Kempf (1962, 1967) described two new species from southern Brazil; Taylor (1980) added to the knowledge of the Australian and Melanesian species; and Wilson and Brown (1985) described a new species from Singapore and gave a detailed account of the behavior of a captive colony. I now recognize 10 "species" in Costa Rica. They show complex and subtle morphological patterns, including sharply parapatric distributions along elevational and moisture gradients, and what may be patterns of introgression at hybrid or contact zones. Thus other authors might treat them as subspecies or single polytypic species. The details of these patterns are treated under the individual species accounts.

The characters I use in differentiating the species are size and proportions, head shape, pilosity patterns, and face sculpture.

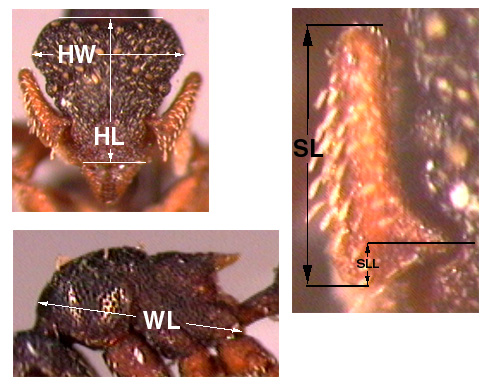

Size and proportions: Although I have not made extensive measurements, I have measured a set of variables for at least one worker of each species. The variables are:

Head length (HL): length of head measured in full face view, along median axis, from anterior border of clypeus at midline to line tangent to posteriormost lobes of vertex.

Head width (HW): width of head across widest point posterior to eyes.

Scape length (SL): maximum length of scape, including anterior lobe.

Scape lobe length (SLL): Along same axis as scape length measurement, distance from anterior border of anterior lobe to perpendicular line crossing approximate midpoint of scape base, where it goes under frontal carinae.

Webers length (WL): distance from anterodorsal border of pronotum to rearmost extension of posteroventral propodeal lobes.

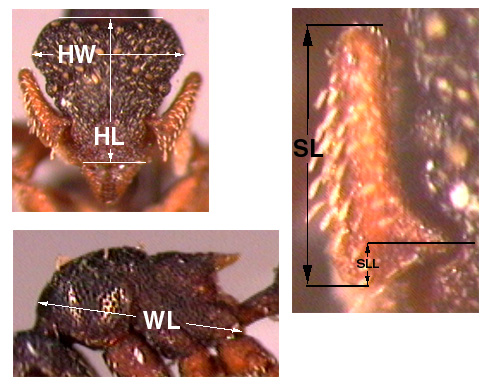

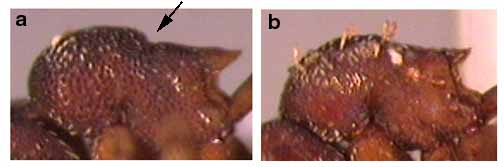

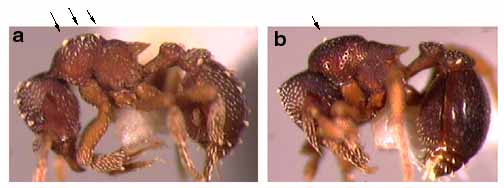

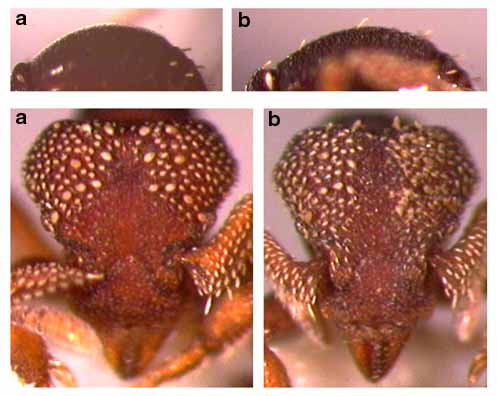

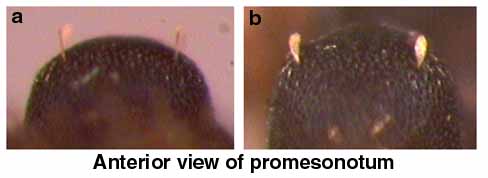

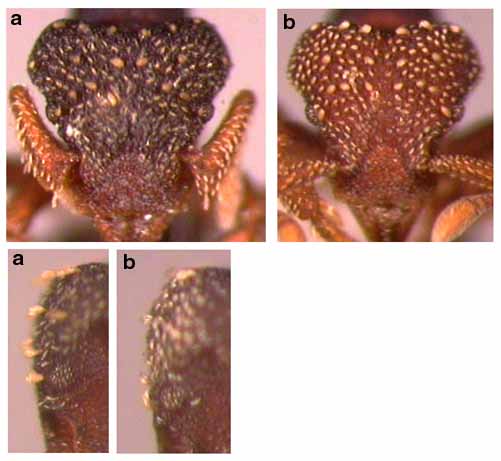

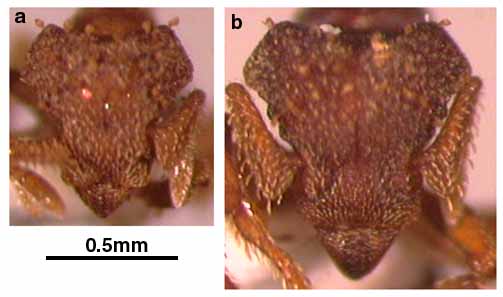

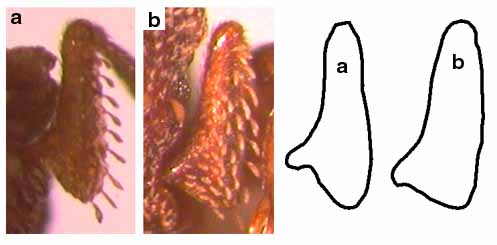

Head shape: the lateral margins of the head posterior to the eyes vary from strongly angular (left figure below) to more smoothly rounded (right figure below).

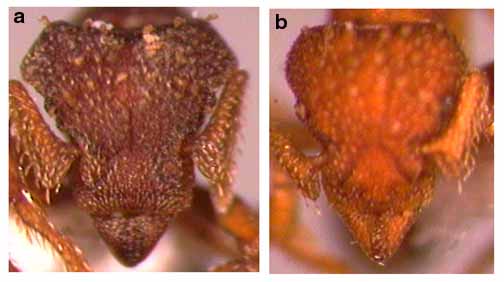

Pilosity: as described above, Eurhopalothrix workers often have two kinds of setae: ground pilosity and erect specialized setae. The erect setae usually occur in symmetrical patterns on the face (see figure below), mesosoma, and gaster. The specialized setae may be lost due to wear, but one can often rely on the symmetry to see where lost setae should be. The pattern of setae on the face is often very important. The specialized setae may be large and uniform in size, while the ground pilosity is composed of filiform hairs or otherwise very inconspicous. Conversely, the specialized setae may be reduced in size, while the ground pilosity is larger, lifted slightly off the surface, and very conspicous. In the latter case, the specialized setae are not clearly differentiated from the ground pilosity, although with close inspection one can usually discern which setae are the specialized ones.

(figure adapted from Brown and Kempf 1960)

Face sculpture: the face may be (1) uniformly punctate, giving the face a dull, granular look; (2) punctate, with the puncta more widely spaced, with shiny interspaces between the puncta; or (3) shallowly rugose (wrinkled).

10a. Scapes covered with uniform appressed spatulate setae, lacking differentiated row of specialized setae on anterior margin: JTL-005

10b. Scapes with differentiated row of specialized setae projecting from anterior margin: 50

50a. Propodeal suture distinctly impressed; promesonotum and propodeum not forming a single convexity in profile: 100

50b. Propodeal suture not impressed; promesonotum and propodeum forming a single convexity in profile: 300

100a. Promesonotal dorsum with 3 pairs of broadly spatulate setae; face uniformly punctate; specialized setae on face conspicuous, broadly spatulate and differentiated from ground pilosity; color orange red: bolaui

100b. Promesonotal dorsum with at most 2 pairs of specialized setae, which are spatulate to filiform; face punctate or rugose; specialized setae on face variable, but often small and not clearly differentiated from ground pilosity; color often dark red brown to nearly black: 150

150a. Face with shallow to distinct median sulcus; surface of sulcus punctate with intervals between puncta shiny: 175

150b. Face evenly convex, without sulcus; face rugose: 200

(SEM inserts are not of these species, but for illustrative purposes only)

175a. First gastral tergite devoid of erect specialized setae; medial sulcus of face weakly impressed; ground pilosity of face sharply restricted to vertex lobes; posterior row of specialized setae on face composed of 4 setae, no trace of an additional lateral pair: JTL-009

175b. First gastral tergite with at least a few erect specialized setae, usually a posterior row of 2-4 and a pair at mid-disk; medial sulcus of face more strongly impressed; ground pilosity of face more extensive, extending further toward clypeus; posterior row of specialized setae on face composed of 4 distinct medial setae, and usually a smaller lateral pair: JTL-010

200a. Specialized setae of promesonotum and gaster sublinear, not or only weakly clavate: JTL-001

200b. Specialized setae all clavate to spatulate: 250

250a. Specialized setae of face of nearly uniform size, conspicuous, clearly differentiated from small ground pilosity: schmidti

250b. Specialized setae of face small, weakly differentiated from conspicuous, suberect ground pilosity: JTL-008

300a. Sides of head above eyes strongly angular: 350

300b. Sides of head above eyes rounded, not strongly angular: JTL-002

350a. Relatively smaller (HW 0.67, n=1); anterior lobe of scape relatively larger (SLL/SL = 0.26, n=1); first gastral tergite with ground pilosity clavate, relatively conspicuous; ground pilosity of face, when visible, evenly distributed on clypeus: JTL-006

350b. Relatively larger (HW 0.78-0.88, n=2); anterior lobe of scape relatively shorter (SLL/SL = 0.17, n=1); first gastral tergite with ground pilosity sparse, thin, relatively inconspicuous; ground pilosity of face restricted to vertex, absent on clypeus: gravis

Literature Cited

Bolton, B. 1998. Monophyly of the dacetonine tribe-group and its component tribes (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Bulletin of the Natural History Museum London (Entomology) 67:65-78.

Brown, W. L., Jr., Kempf, W. W. 1960. A world revision of the ant tribe Basicerotini. Stud. Entomol. (n.s.) 3:161-250.

Hoelldobler, B., Wilson, E. O. 1986. Soil-binding pilosity and camouflage in ants of the tribes Basicerotini and Stegomyrmecini (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Zoomorphology (Berl.) 106:12-20.

Kempf, W. W. 1962. Miscellaneous studies on neotropical ants. II. (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Stud. Entomol. 5:1-38.

Kempf, W. W. 1967. Three new South American ants (Hym. Formicidae). Stud. Entomol. 10:353-360.

Snelling, R. R. 1968. A new species of Eurhopalothrix from El Salvador (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Contr. Sci. (Los Angel.) 154:1-4.

Taylor, R. W. 1980. Australian and Melanesian ants of the genus Eurhopalothrix Brown and Kempf - notes and new species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. Aust. Entomol. Soc. 19:229-239.

Wilson, E. O. 1956. Feeding behavior in the ant Rhopalothrix biroi Szabo. Psyche (Camb.) 63:21-23.

Wilson, E. O., Brown, W. L., Jr. 1985 ("1984"). Behavior of the cryptobiotic predaceous ant Eurhopalothrix heliscata, n. sp. (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Basicerotini). Insectes Soc. 31:408-428.

Page author:

John T. Longino, The Evergreen State College, Olympia WA 98505 USA.longinoj@evergreen.edu