Date of this version: 5 June 2007.

| Genus List | Key to Species | Species list |

The dolichoderine genus Azteca is a strictly neotropical group of arboreal ants (Emery 1893, Forel 1928). They are abundant in lowland habitats from Mexico to Argentina, occurring as both generalized foragers and as specialized inhabitants of myrmecophytic plants. Azteca species exhibit a variety of nesting habits, including the construction of carton nests, the occupation of live and dead plant stems (Forel 1899, Ule 1901, Emery 1913, Davidson 1988, Ayala et al. 1996), and the formation of ant gardens. Ant gardens are arboreal ant nests which sprout epiphytes from carton nest material (Ule 1901, Wheeler 1921, Longino 1986, Davidson 1988, Corbara et al. 1999, Kaufmann & Maschwitz 2006). Striking cases of symbiosis occur between Azteca and highly specialized myrmecophytic plants, the most notable case being the relationship between Azteca and Cecropia (Mčller 1876, 1880-1881, Bequaert 1922, Wheeler 1942, Benson 1985, Longino 1991a, b). Also, Azteca ants have developed complex trophic relationships with many species of coccoid Hemiptera (Wheeler 1942, Johnson et al. 2001, Davidson et al. 2003). Azteca workers are often found tending mealy bugs (Pseudococcidae) and soft scales (Coccidae). For Azteca species that nest in live stems, the interior walls of the nest are often encrusted with mealy bugs and scales. Species building carton nests and ant gardens maintain dense populations of mealybugs and scales under the carton of the main nest or under small carton "pavilions" scattered over the vegetation. Very little attention has been paid to the taxonomic diversity of Coccoidea associated with Azteca, and usually only cursory observations of their presence are made during field collections. Because of the richness of the ecological interactions among Azteca, plants, and hemipteran symbionts, Azteca species have been and will continue to be subjects in the study of adaptation and coevolution, and therefore taxonomic work on the genus is particularly important.

The taxonomic bounds of the genus have not changed since its inception (Forel 1878, Shattuck 1992). Members of the genus can be recognized by the combination of (1) a thin, somewhat flexible cuticle, (2) anterolateral margins of clypeus extending anterior to mediolateral regions (with the exception of the aurita group, as reported here), (3) mandible with 7-9 teeth, (4) at least larger workers with cordate head shape, with margin of vertex concave, (5) surface sculpture (other than on mandibles) smooth, micropunctate, microalveolate, or combinations of these, (6) the total absence of coarse surface elements such as spines, tubercles, carinae, rugae, striations, or large puncta, (7) a distinctive petiole which is strongly sloping anteriorly and has a rounded posteroventral lobe, and (8) worker caste polymorphism.

The Asian genus Philidris (former Iridomyrmex cordatus group) is highly convergent with Azteca. In contrast to Azteca, the anterolateral margins of the clypeus are posterior to the mediolateral portions, and the mandible has 10-12 teeth. Male characters (Shattuck 1992) and recent molecular evidence (P. S. Ward, pers. com.) ally Philidris with other Asian dolichoderines and confirm that the similarity is due to convergence.

The relative clarity of the generic status of Azteca is not mirrored in species-level taxonomy. Several factors contribute to taxonomic confusion in Azteca, some historical, some biological. The only revision of the genus Azteca is that of Emery (1893). Over 140 species-group names were subsequently published by Forel, Wheeler, and others, with no attempts at revision. Many species were described from workers only, with no biological data. Since it is often particularly difficult to separate Azteca species with workers only (Longino 1991a, b, 1996), many named Azteca species are difficult to circumscribe.

Wheeler and Bequaert (1929) belatedly stated "Apparently the females [i.e., queens] furnish more reliable characters for identification than the workers in the genus Azteca." An analogy can be drawn between the taxonomy of Azteca and the taxonomy of many plants. Botanists typically shun sterile material because it is often more plastic within species and less differentiated between species than reproductive material. Such is the case in Azteca. Workers are polymorphic within colonies, and colonies exhibit prolonged ontogenetic changes in worker morphology (pers. obs.). In contrast, queens are much less variable morphologically and exhibit strong interspecific differences. Within a single locality, species with strongly differentiated queens may have workers that are barely distinguishable.

Correlated with sharp differences in queen morphology are distinctive nesting habits. Nesting habits show great interspecific variation and little intraspecific variation. For example, queens of Cecropia-inhabiting species colonize very young Cecropia saplings. These queens are often very abundant in the environment, colonizing saplings and apparently competing for domination of saplings (Longino 1989b). I have made extensive collections of neotropical arboreal ants by breaking live and dead branches, searching for carton nests and ant gardens, and dissecting other myrmecophytes such as Cordia, Acacia, Triplaris, Tococa, and Ocotea. The Azteca species which dominate Cecropia trees are found only in Cecropia trees. In spite of high queen density and competition for saplings, I have never encountered one of these Azteca species, either colonies or founding queens, in any plant cavity other than that of a Cecropia. Thus, when only workers are available, biological data on nest site can be of critical diagnostic importance.

Because of the unreliability of worker morphology, many names in Azteca may remain in nomenclatural limbo indefinitely. Identities of species based solely on a type series of workers, with no data on queen morphology or nesting behavior, will only be resolved by a thorough understanding of the subtle differences between workers of all the species at the type locality. In the mean time, it is important to have species descriptions and a nomenclature for this important genus of neotropical ants.

I have carried out a series of studies on Azteca taxonomy and natural history (Longino 1989a, 1991a, 1991b, 1996, 2007), with an emphasis on the fauna of Costa Rica. These web pages review the entire Azteca fauna of Costa Rica.

Methods

Measurements reported in these pages were taken over a long period of time, with varying equipment and precision. Older measurements, including measurements of most types during a visit to European museums in 1990, were taken with an ocular micrometer and are precise to the nearest 0.01mm at best. More recent measurements were made with a micrometer stage with digital output in increments of 0.0001mm. However, variation in specimen orientation, alignment of crosshairs with edges of structures, and interpretation of structure boundaries resulted in measurement precision to the nearest 0.01 to 0.005mm, depending on sharpness of the defined boundary. When measuring workers, larger workers of a series were haphazardly selected. Only one worker from a colony series was measured, and when a species was known from multiple localities, workers were selected from different localities. All measurements are presented in mm. Measurement lists in individual species accounts show the sample size, followed by the median and range (in parentheses) for each metric variable. When sample size for a particular variable differed from the common sample size, it is given following the range, within the parentheses. Except where noted, measurements refer to Costa Rican specimens and may not encompass variation across the entire geographic range.

The following terminology and abbreviations are used:

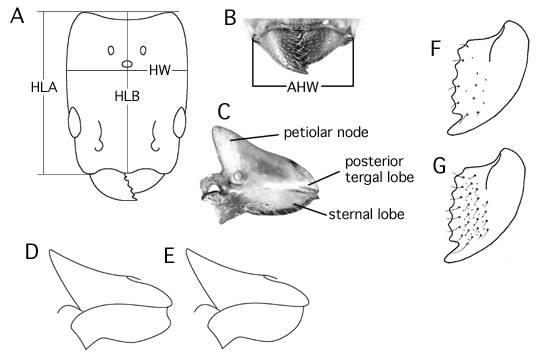

HLA: head length in full face view; perpendicular distance from line tangent to anterolateral clypeus lobes to line tangent to posteriormost extent of vertex lobes (Fig. 1A). This measure is chosen because the anterolateral clypeus lobes are always visible, while the anteriormost extent of the medial lobe may be obscured by the closed mandibles.

HLB: medial head length; same as HLA except from anteromedian instead of anterolateral lobe of clypeus (Fig. 1A). This measure is important for the A. aurita group, where the lateral lobes are not well defined and the median lobe is strongly protruding. For most Azteca HLA and HLB are very similar.

HW: head width; in full face view, maximum width of head capsule above eyes (Fig. 1A).

AHW: anterior head width; distance across anterior foramen of head, measured across outer edges of mandibular condyles where they insert; measured in anterior, oblique, or dorsal view (Fig. 1B).

SL: scape length; length of scape shaft from apex to basal flange, not including basal condyle and neck.

EL: eye length, maximum length of eye.

OCW: width of median ocellus.

MTSC: metatibia seta count; with tibia in anterior view, such that outer (dorsal) margin is in profile, number of erect to suberect setae (distinct from any underlying pubescence) projecting from outer margin.

MNSC: Number of erect setae on mesonotum of workers. Very fine, short setae are included in the count, and often these fine setae are only visible at particular angles and proper lighting. Counts are made up to 19 setae, after which specimens are scored as => 20.

CI: cephalic index; 100*HW/HL.

SI: scape index; 100*SL/HL.

Standard measurements of head width, head length, and scape length are of paramount importance for distinguishing Azteca species.

Palpal formula is 6,4, 5,3, or 4,3 (maxillary palp, labial palp).

Surface sculpture: Mandibles are generally shiny at the masticatory margin and microareolate or otherwise sculptured at the base. Sculpture of the intervening region varies interspecifically and can be of diagnostic value. This region may have widely spaced small puncta, or small puncta with a few large puncta concentrated near the masticatory margin, or many large puncta (Fig. 1F,G). The interspaces may be shiny, microareolate, or roughened with longitudinal acicular sculpture. A few weak grooves are often visible on a generally shiny surface, but this contrasts with species which have strongly roughened mandibles. Mandibles of the latter appear opaque. The head and mesosoma may be densely micropunctate, imparting a somewhat dull surface, or rarely completely smooth and shiny.

Pilosity and pubescence: Azteca generally have a layer of short pubescence throughout, showing interspecific variation in density. The distribution of pilosity, referring to setae that are distinct from the underlying pubescence, is used extensively in this treatment. Important areas for variation in pilosity are the dorsal surface of mandible, lateral and posterior margins of head in full face view, dorsal profile of mesosoma, outer surface of metatibia, ventral margin of petiole, and third and fourth abdominal terga.

Petiole shape: the shape of the sternal lobe and its relation to the posterior tergal lobe (Fig. 1C,D,F) vary among species. To see the petiole requires a clear view of the lateral profile. On dried specimens the gaster is often elevated and tightly appressed to the petiole, which obscures the view. The gaster must be pulled away or removed, and the metacoxa pushed forward or removed. The line of fusion between the tergum and sternum is usually visible, and this is oriented horizontally for a standard lateral view.

Page author: John T. Longino longinoj@evergreen.edu

Date of this version: 5 June 2007.

![]() Go back to top

Go back to top